Last week, I had the privilege of dealing with a particularly fun problem where our Oauth flow for our new application wasn’t working correctly. The problem manifested itself like this:

- Logging into the mobile app pointed to a local dev environment worked fine.

- Logging into the mobile app pointed to our “live” development env also worked fine.

- Logging into production didn’t.

Tapping on “Log In” opened the form. Submitting the form and doing 2FA worked… up until the point where the app should have redirected back to the app. But it never did. It just sat there.

Ideas swirled around: was there a different configuration for production that in our other environments? Well, of course there are always some differences. But which ones mattered?

There were a number of things that we started trying… we tried undoing recent updates. We had added some stuff that played with the login session. But doing that didn’t seem to make a difference. We couldn’t actually get it to break again except in production.

What is production doing?

What seemed most important was to figure out what production was actually doing. The best way aside from things like logs (which, there were no errors) is actually look at what’s going over the wire. To accomplish this, I pulled out Charles Proxy. I downloaded the TestFlight version of the app, got the certificates installed and set up SSL proxying.

After saving the traffic capture from the production app, we recreated the same thing with a local copy connecting to our testing environment and compared.

The traffic from the testing environment didn’t really seem all that different. The production environment had a bunch of additional headers in it, but nothing stood out.

What was known at this point was that the issue manifested at the last step of the authentication flow. We thought that perhaps a change to the final step caused the issue, but after some additional testing and trying a different fix, it didn’t fix it at all.

Claude, giver of ideas

Early on in the process, I fed the final responses from the servers to Claude and asked if there were any differences that could possibly have explained the issue.

It gave me 3 options:

- CORS headers

- The CSP (Content Security Policy) header

- A strict

frame-ancestorsdirective. - A strict

form-actiondirective. - Some sort of rewriting happening by Cloudfront

Now we had to figure out what to do with this information. Claude was almost certain the issue was the CORS header. It was not.

The issue: the CSP’s form-action directive

I’ll save you the entire 6 hour ordeal and skip right to the end: in our case the form-action directive was too strict. Our form-action directive looked like this:

form-action 'self' https://*.production.com;

But wait, you might say, we’re talking about a redirect here. Yes, that is true. And this was ultimately the reason why this ended up as the last thing we tried.

The Content Security Policy W3C Working Draft says this about form-action:

The form-action directive restricts the URLs which can be used as the target of a form submissions from a given context. The directive’s syntax is described by the following ABNF grammar: (emphasis mine)

The form was submitting to the same page. So this really, truly didn’t seem like the source of the issue. However, doing some additional research on this led me to Mozilla’s page on the form-action directive which displays this on the very top:

Warning

Whether form-action should block redirects after a form submission is debated and browser implementations of this aspect are inconsistent (e.g., Firefox 57 doesn’t block the redirects whereas Chrome 63 does).

Scrolling down the page reveals that, indeed, Safari (and therefore WebKit), also blocks redirects as part of form submissions.

To be clear, after the user enters their 2FA, they tap the button and:

- The form POSTs to the same URL that they are currently on.

- If the 2FA code checks out, then that form redirects to another URL.

- That URL then “completes” whatever flow the user started, and redirects them to the correct Oauth client ID redirect URL.

It is that final redirect that is ultimately getting blocked.

Testing the theory

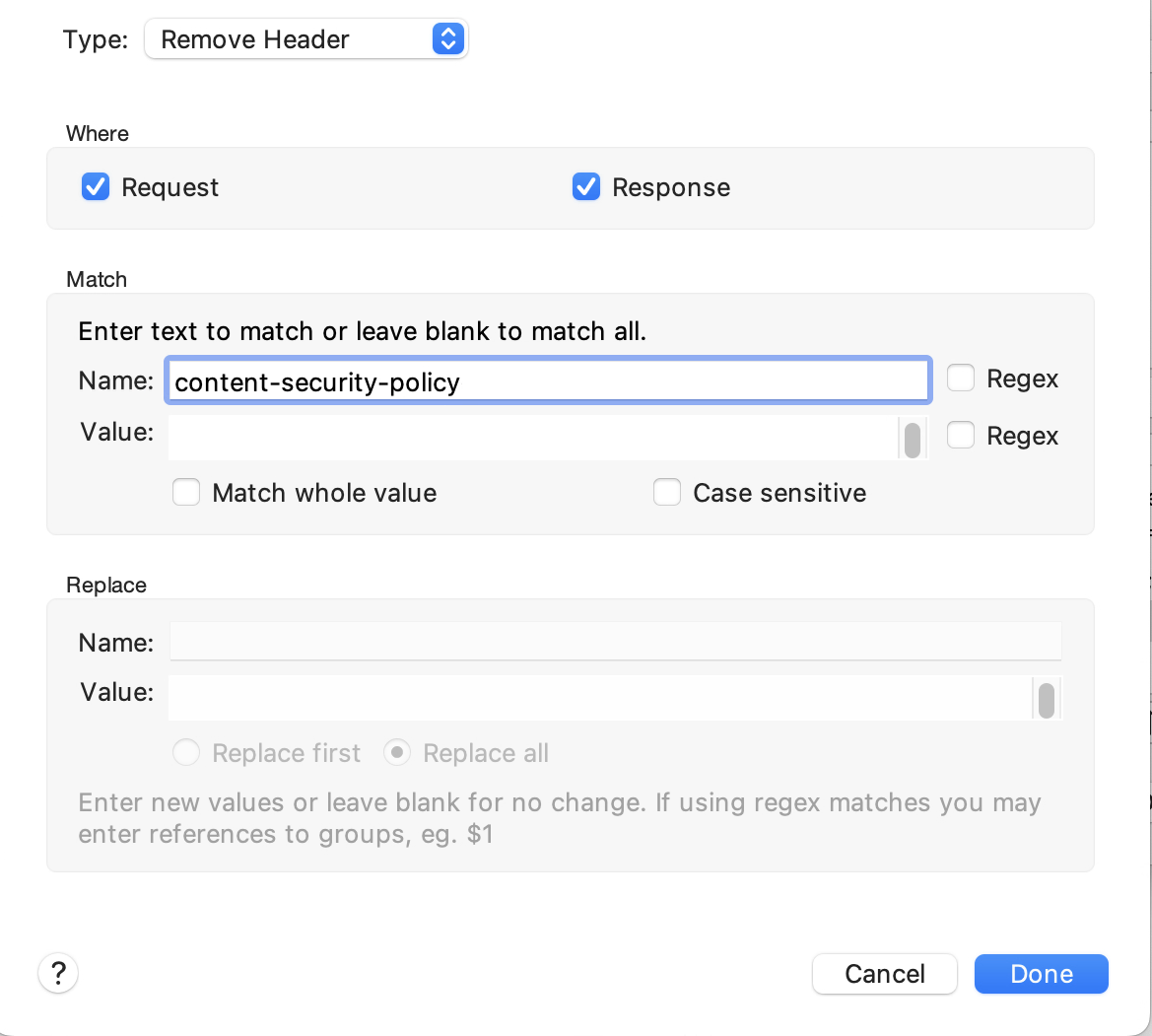

So, OK… how can we test this theory without modifying production? Well, here again, Charles Proxy provides the rewrite tool. With it, we can actually just remove the Content-Security-Policy header from the traffic coming from production:

This worked exactly like you would expect it to. It rewrote the responses and removed that header. And, to our great elation it fixed the problem.

Can we reproduce it, though?

OK, so it seems to fix the problem, but I wanted to make doubly sure that it really truly fixed the problem. I still wanted to positively reproduce the issue.

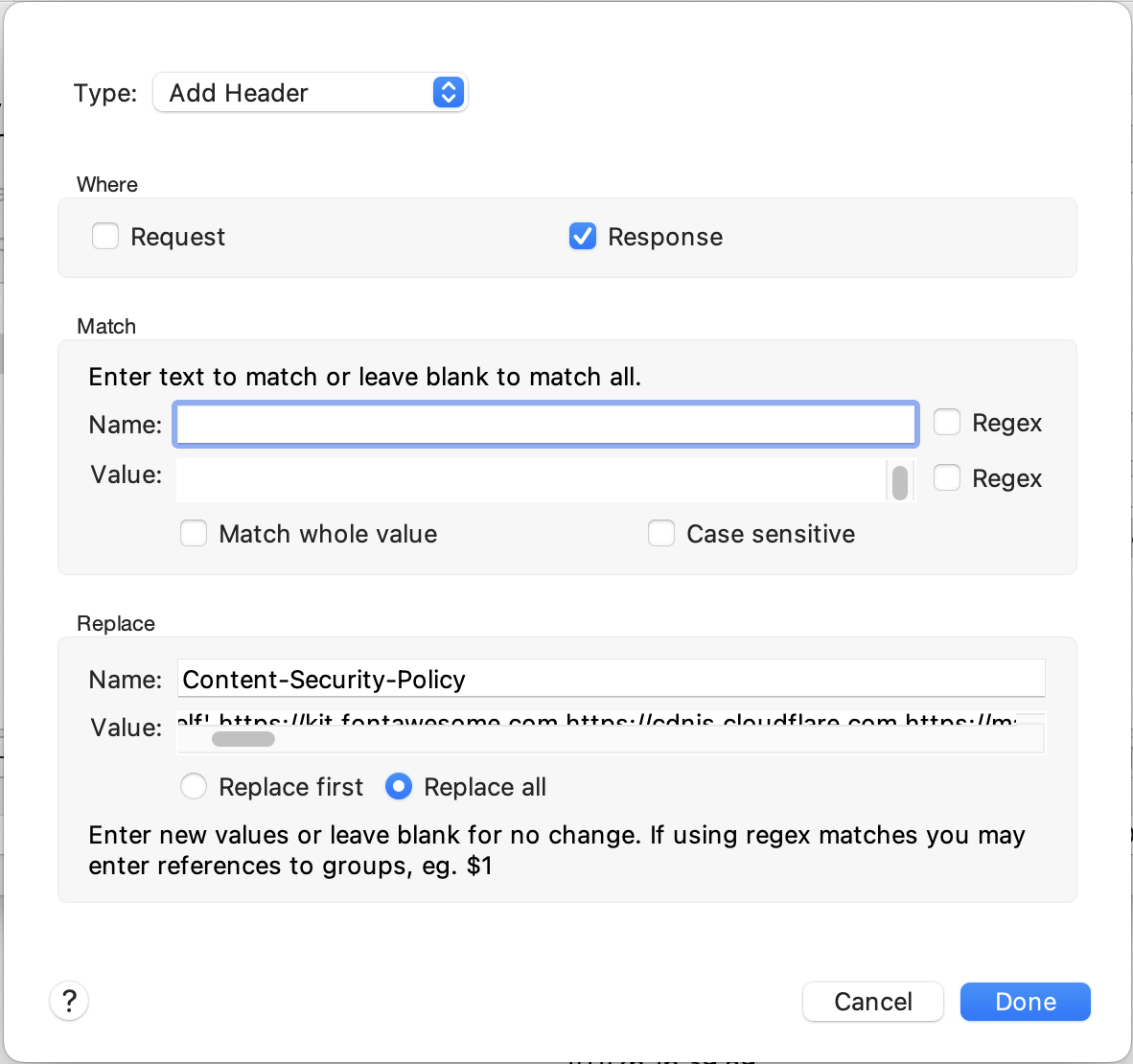

If removing the header fixed the problem, then adding the header back to an environment that already was working… that should break it right?

Again, Charles to rescue by letting me add that header back to traffic on a working environment:

And, also to our great elation, this caused the same problem to surface in a non-production environment.

So what was the “real fix?”

In the end, we needed to add our custom redirect URL managerapp: to the form-redirect directive like this:

form-action 'self' https://*.production.com managerapp:;

We tested this again using Charles Proxy and then had DevOps roll out this change. Everything started working as expected.

Takeaways

- Having production and dev environment running images doesn’t mean the are the same.

- Specs have interpretations and sometimes reading the spec isn’t enough.

- We didn’t “waste” the day figuring out it wasn’t a code issue—we learned and documented things.

- A good proxy is a must-have for native app development.

App Container didn’t help

We run containers for local dev and for our other environments. But this doesn’t mean that the configurations are the same. In this case, the extra headers were not added to the application, but were added by the WAF after the fact. These changes weren’t documented anywhere: it was tribal lore.

Implementations of specs vary

The original CSP Level 3 spec doesn’t say what happens with redirects. Even Firefox still handles it differently. Mozilla’s docs were great here.

Debugging isn’t a waste

At the end of the day, we ended up learning and reinforcing several skills and getting to know each other better:

- A non-mobile dev got the app set up locally on their machine, validating existing docs.

- We learned how to set up Charles Proxy to work with simulators and physical devices.

- Got to learn how to use the Rewriting tools of Charles Proxy.

- Knowing that it wasn’t our code helped to reinforce the idea that the test coverage we had actually did a good job.

- Interacting with people and seeing how they deal with frustrating experiences is a moment when friendships get forged.

Charles Proxy saved the day

Knowing how to set up a proxy and having a good proxy was key to not only figuring out what the problem was but also for reproducing the problem and testing and validating the solution. If you have never set up a proxy, I’d encourage you to do so. While every browser has some level of developer tooling, a good proxy works across browsers and devices and can give you a level of control that the browser dev tools can’t.